Pages

Wednesday, 27 June 2012

Prometheus: Ridley Scott won't have his liver picked for this one

The sound (as separate from the music) is awesome as well. You are really trembling in your seat when a spaceship blasts overhead.

And it's well paced in terms of action, building up in steady crescendo. It's a chain reaction with few let ups. I'm still releasing tension. So that part of the movie worked very well.

Plotwise, well...

...spoilers from here

The actions of the scientists are just unbelievable unprofessional. No archeologist worth his salt would interfere with the find. Noone would just take of their helmets (especially not later, when you've decided this is a hostile environment).

Also, how can two men get lost in a system that is being mapped by one of them, and while they have constant contact with the ship's crew?

Since when do biologists try to make friends with animals clearly showing their not friendly when you know the environment is hostile?

Why does the captain leave his post when there are lifeforms at large and two of his men out when he know something bad has happened out there?

Why does the face of the decapitated alien look serene, rather than smashed?

But more basically: why are cannisters with very dangerous weaponry neatly arrayed in a room with ceremonial function? And why would people try to hide there?

And how does the captain suddenly understand that the base is meant as a WMD production facility? He hasn't been down in the base and not put any time into tying all the ends together, rather the opposite. He's ignored lots of info.

Ok, suppose you just auto-removed an alien embryo and then had your belly stapled... You then run into the guy that's tried to freeze you in while carrying the embryo. You then just talk to him? You don't try and put a bullet in his head?

And you don't tell anybody of the squid lingering in the operation room? Not even the cleaner?

I also see serious issues of continuity with Alien (the sequel). The guy they're supposed to find in the control room (I always thought he was manning the gun, but that's another story) in Alien. has left. In Alien, nobody notices the remnants of the Prometheus, close by, let alone the human remains of the prometheus crew in the control room.

And actingwise, the performance by David the android with his love for Lawrence of Arabia is very good. All the other roles, I think, are forgettable.

oh well...

I just don't know why Scott chose to go this way. The original Alien works much better in terms of suspense and pacing, while at the same time keeping the movie coherent. The acting gets much more time to shine making it interesting from that point of view as well. This all makes the choices and actions of those involved much more believable.

Is the modern blockbuster just incapable of telling a good story, so as not to interfere with the action sequences? Makes me sad.

But let's start on a positive note: the Engineer at the start of the movie, who drinks a cup and dissolves. What was he drinking. Why did he do it? Guilt? Suicide? As a means to start the outbreak? Fascinating and unresolved in the movie.

This is just my take. There's a much better review from a more cinematically versed Scott fan that I really recommend.

Monday, 25 June 2012

Megagame Operation Goodwood 1944

Nobody can tell whether he expected a breakthrough but it was useful anyway in tying down the armoured reserves that the Germans might otherwise have employed against the Americans. It is best known for its massive opening air bombardment and employment of armour, which in the end didn't supply very impressive results.

On May 14th 2011 me and 60 others tried to recreate this battle in two acts: the first consisting of a planning game and the second of the execution of those plans. Since the historical attack was called off after three days due to torrential rains, this could all be fitted nicely in a morning and an afternoon session.

The planning session involved a pressure cooker attempt to set out the outline for the battle, with the British Second Army commander (Dempsey) setting the objectives and allocating them to the VIII Corps (O'Connor), consisting of three armoured divisions, and two infantry divisions on the flank.

Once the big picture was available, the corps and division HQs started to work out the details, like establishing mutual boundaries of responsibility, initial dispositions and artillery support. At the same time they needed to liaise with the tactical and strategical air forces at their disposal, number over 2000 light, medium and heavy bombers and appropriately introduced as 'the most powerful attacking force in human history until August 1945'.

Each team consisted of a commander, an operations and an intelligence staff officer. While the first was responsible for making decisions and keeping the unit's war diary, the second was responsible for writing the detailed orders and co-ordinating with adjacent units. The intelligence officer was responsible for seizing up the opposing forces and providing superior and neighbouring HQs with information.

Most players were part of a divisional headquarter team, but on the Allied side there were also teams for VIII Corps, 2nd Army and the air force, while the Germans had a Corps HQ.

The Germans, in the meantime, tried to come up with a defensive plan, which should make optimal use of the terrain: open ground gently sloping upwards to the Bourguebus hills dotted with fortified villages. A perfect hunting ground for 88mm antitank guns and hull down panzers.

By early afternoon the plans had crystalised into tactical positions and initial orders for individual battallions and batteries. These were then communicated by the team umpires to the main map for execution. The game was set to begin.

To each division was attached a team umpire who interfaced between the team and the main map. The operations player would give him the orders for units and explain their intentions. The umpire would then resolve these orders at the main map and return with the outcome in the form of a narrative report, revealing as little as possible of the game system.

So rather than 'you had 24 combat points and your opponent 13, and you rolled a 6 so you now have a Total Succes result' a player would be informed that "the 5th Royal Tank Regiment brigade group has attacked at dawn in perfect formation and while the overwhelming artillery suppressed enemy opposition, the infantry charged into the village driving the enemy before them with negligible losses. The village was occupied and prepared for defense as ordered. Troops are in good spirits."

The battle started with establishing the effect of the infernal aerial bombardment at the start of the first turn, or the morning of 18th July 1944. In the picture, you can see the bombardment counters on the main map, measuring 2 square kilometers each. Depending on the number of squadrons allocated to each counter (up to 20!) the units within the bombed area suffered casualties and immobilisation.

The umpires for the British team strolled back for early tales of the incredible roar of the air fleets passing overhead and the massive fountains of fire and death erupting from the hills and villages before them. The German teams, on the hand, received terrifying reports of the carnage and destruction around them, the loss of precious tanks and artillery, but also in many cases of merciful exclusion from allied attention. Then the infantry and armoured attack rolled in and the liaison umpires returned to the main map.

I participated as a team umpire to 7th armoured division. Like the players, I would be so busy that I had little idea of what happened to other player teams, so my story is different from what was experienced by the Canadians on the far right flank, let alone the German teams.

The game was executed in three turns (morning, afternoon, night) per day. Based on the team orders the units were moved until their objectives or, more likely, until they met opposing forces. Then combats were worked out based on the combat strength of the units, tactical situation and support from artillery and air.

As was historical, the best attacks were made by relatively fresh units, combining infantry, tanks and artillery with copious air support. As we found out, the latter factor would prove decisive in most cases and us umpires quickly adopted a procedure of first comparing the support on both sides to determine whether it was worth going through the rest of the combat factors.

It was hardly unexpected that the British would break in after such the bombardment, but the initial attack saw 7th Armoured Division (the famous Desert Rats) drive deeply into the German gap, while 11th Armoured Division faced tougher opposition. However, a big enough gap was opened between them so that the third armoured force, Guards Armoured, could slip in between them as planned. The afternoon saw the latter two divisions drive rapidly forward, while 7th Arm was welcomed by a strong German counter attack including Tiger tanks.

While the morning and afternoon turns were frantic due to just half an hour to receive reports from the team umpires, discussions with neighbouring and superior HQs, coordination of air support and writing of new orders, the night turns proved a bit more relaxed and the commanders were able to take stock of the situation. The first night both sides struggled frantically to shift reinforcements and prepare for next morning's attacks.

7th Armoured Div opened the second day, 19th of July, with a vicious attack on the Germans that had driven them back the day before, and the Typhoons assigned to them had a field day picking off the retreating Tigers. But again, the afternoon brought them a counter attack that bloodied their noses. This time it was 12th SS Panzer division. It was decided that 7th Armour's flank was too exposed and it would halt until 3rd Infantry Division on its left would come up. Meanwhile the Guards and 11th Armoured had bypassed 7th and reached the foot of Bourguebus ridge.

July 20th, the third day of the offensive, was a day of heavy, yet dispersed German armoured counterattacks that managed to delay and halt further British advances, but at frightening costs in tanks. As before, 7th Armoured received a withering attack to its exposed flank by the SS in the morning, but managed to crush these troops in the afternoon with the help of the infantry division that finally had moved up.

So when night and pooring rain fell over the battlefield, Monty could be unexpectedly satisfied with the result. To paraphrase a famous Dutch football player and coach: the Allies can't win Goodwood, but the Germans can lose it.

Although the British armoured divisions had taken considerable losses, their brewed up tanks could be easily replaced, while the Germans had effectively lost some 75% of their precious tanks and thereby their ability to counterattack in force. And despite the frontline having stabilised, the allies had made worthwhile advances and would keep the German elite divisions tied up far away from the American breakout that was to come.

The day was wrapped up by the senior commanders giving their perception of what went on during the battle and with many players having a peek at the main map. This was the first glimpse they would have of the real status of their troops. During the day they would have had to figure out their battleworthiness through the team umpire.

Games of this size (30 players and up) are called megagames. We have organised a few in the Netherlands but Megagame Makers in London organises about four of them each year and have been doing so for thirty years. For more information on past and future megagames, see their website.

Note: I visited Normandy in the summer of 2011 and had a quick tour of 15 minutes driving on the outer edges of the battlefield, which happen to be the major highways to the west and south of Caen. I was surprised how small the battlefield was and how open compared to the more closed terrain on the eastern edge. A well sited 88mm gun could cover a large stretch.

This post was published earlier on Fortress Ameritrash

King John and the siege of Rochester Castle

This led us to the rather unknown First Barons' War where John defended his rule against a rebellion by 2/3rds of his vassals, combined with Scotland and France. And all this happened after John had signed the Magna Carta (which surprised me), although he did so half-heartedly.

Also, it turned out that John had his enemies largely beat by the time of his sudden death late in 1216. This included the French Dauphin who had invaded Britain at the behest of the rebels.

On the way back I picked up Ralph Turner's King John, England's evil king? as well as Carpenter's The Struggle for Mastery 1066-1284 at Gatwick. This is proved fascinating reading. So far I'm learning about John's early life and administration of England and the French possesions (basically Western France from Normandy to the Pyrenees).

The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: the Middle Ages also has a few pages with great maps showing the conflict and Hillaire Belloc's Warfare in England provides some brilliant insights in the geographical importance of royal castles such as Windsor and Dover.

All this makes for a great game, as the whole thing is finely ballanced between John's control of strategic castles and highly trained and mobile army against a host of enemies which are in the end mostly a result of him being an utter prick. His death may even have saved England from French domination as John's young son Henry (III) was a much more agreeable monarch than French Dauphin Louis.

John has a rather bad reputation, which doesn't entirely do him justice. He was an utter prick, but so were his father Henry II and brother Richard Lionheart. Richard's saving grace was his generosity, but his generous spending on his crusade, then his bail from captivity, followed by continuous war against France to retain hold of Normandy plundered the treasury.

On the opposing side the kings of France in this era were able to extend their hold over France and increase their income, slowly swinging the balance of war in their favour.

So John inherited a mostly bankrupt country from which he tried to squeeze the last drops.

The treasury was mostly filled from the English possessions as the power of the kings was greater here than in their other lands of Anjou, Normandy and Acquitaine. This was always unlikely to ingratiate him with the barons.

This is a situation reminescent of the Spanish Habsburgs who drained Castile in the 16th and 17th centuries to fight their wars abroad because it was the only part of their empire they could control. In that sense the Angevin Empire was as weak as other patchwork realms where local elites jealously guarded their ancient rights, and may not have stood much chance of surviving longer than the half century it did.

John's character didn't help, but he was a sound administrator and a capable commander, as his early campaigns in Normandy show, but even more so in 1215-1216, where he combined a small but high quality field army with a carefully laid out system of royal castles that allowed him to race from Rochester to Edinburgh in just over a month and then back south again in as much time. He also used his strategic mobility to outmaneouvre the rebels and troops of Louis in 1216.

Another tip is Lewes, which also has a nice castle and sets the scene for the first battle in that other Barons' War (1264).

This post was published earlier (in a slightly different form on Fortress Ameritrash

Sunday, 24 June 2012

Stalin's preparations for war in the west, review

This book´s main contribution lies in the daring attempt to bring together all the developments relevant to the rearmament of Soviet Russia in the 1930s in one coherent frame. Furthermore, Musial contends that after the failure of autonomous revolution in the early 1920s, Bolshevik doctrine leadership under Staline became that the Red Army would be the instrument to spread the revolution by armed force. Finally, Musial gives an interesting view on the chain of events leading up to the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Despite Stalin´s long term intention to strike west, Hitler´s invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 cannot be defended as a preventive strike.

Musial starts out the argument with the attempts of the new Soviet leadership trying to export its revolution to the west. After fighting off the White forces and foreign interventions, Soviet Russia in 1920/1 aimed to burst through the new Polish state towards the heartland of the revolution: Germany. Not only did that attempt falter, but by 1924 it was also clear that the revolution in Germany could not prevail by itself.

This forced Lenin & co to reset their course. After a few years of argument between the factions, those with continued commitment to world revolution lost out to Stalin, who aimed at building up a strong socialist state in Russia that could export the revolution by force of arms.

Although the title and Musial suggest that Germany was the primary goal of Soviet plans throughout this period, the book spends surprisingly little time convincing the reader that Germany is indeed the specific target of revolutionary ambition, rather than that the direction is more generally to the West. It isn’t particularly relevant to most of the arguments made in the book, but surprising all the same. Maybe the publisher felt that a more specific focus on Germany was necessary to sell the book.

Musial’s main line of argument integrates fundamental ideological choices with military build up, industrialisation, collectivisation of agriculture and purges. That is an audacious undertaking, because it assumes a coherent and consistent line of policy over almost 15 years. Even with hardheaded bureaucrats like Stalin, this looks a little too much to believe.

Soviet attempts to modernise the army in the 1920s were largely unsuccessful due to economic underdevelopment and inability of the regime to enforce its policies. Stalin's consolidation of power and focus on military expansion provided a more forceful drive.

According to Musial the military build up for the expansion of the revolution required both creating a war industry and securing the homeland. All important developments in the USSR from that moment on flowed logically from this aim.

Rearmament required heavy industries that Soviet Russia no longer possessed and could not recreate quickly enough by itself. The import of foreign capital goods and knowledge required foreign currency. This in turn required higher exports, for which mostly agricultural products were available. But because of the low level of concentration and low level of productivity it was necessary to collectivise Soviet agriculture. Attempts to increase agricultural production in the 1920s had foundered on the unwillingness of the peasants to sell their surplus to the market. With collectivisation Moscow could enforce deliveries from the kolchoz for exports.

Collectivisation was also the solution to the problem of opposition to the Bolshevik regime. After the civil war against the White forces had ended the struggle against the Green revolutionaries continued without a clear victory for the communists. By collectivisation, the regime finally suppressed the Green opposition. Musial goes into depressing detail to show the level of resistance and the ruthless way in which it was dealt with. The kulaks were destroyed, national minorities suppressed or relocated to Siberia.

Musial then looks in more detail at the rearmament programme. The plans of 1927/8 were staggering in their scope but this proved to be mere megalomania. Although an evaluation of the results in 1930/1 reinvigorated the drive, production continued to fall far short of the targets and quality was low. Tank engines broke down so fast, and airplanes crashed so often that training time was limited.

These mechanical breakdowns were not only caused by the low quality of the materials but also by the low level of training among troops and officers. Considering that housing and supply were also neglected, it is no surprise discipline was weak. In the mid-1930s it became clear the Red Army was nowhere near ready to take the revolution abroad.

The failures of Russian rearmament deeply frustrated the Soviet leadership and caused a quest for scapegoats. Accounts of the Red Army in the 1930s always focus on the purges in the military leadership, but a similar fate was met by many officials in the heavy industry and transport services.

No need to say that the purges removed a large part of the experience of the Red Army, but authors like Overy have already argued that the effects of the purges on combat efficiency were limited because many of those officers were not particularly well trained nor motivated anyway. It is also clear that many of those removed from the Red Army returned to duty before and during the war.

To me it is more intreaguing whether the purges were indeed an integral part of the Soviet rearmament drive, or did they have a dynamic of their own? I have too little knowledge of Soviet history to argue either way, but an indication to the contrary would be that the purges affected many more parts of Soviet society than just those related to the military build up.

In the last part of the book Musial covers a lot of ground in short time and this will probably leave a lot of room for discussion.

First of all, Musial contends that Stalin misjudged the threat that the Nazis posed. Through the German communist party, the KPD, Moscow joined the Nazis in undermining the Weimar democracy. And like the Nazis, the KPD opposed the reparations and annexations of the Versailles treaty. The Soviets even continued the economic relationship with Germany after Hitler had come to power in 1933 and accounted for most of German exports of capital goods.

Only in 1934 did Stalin reverse this course as it became apparent that Hitler was there to stay and suppressing the KPD. Stalin then turned to a Popular Front approach to counter fascist movements throughout Europe. He also sought closer ties to the western democracies as a counterweight to German designs to the East. However, Musial interprets his sources as to indicate that Stalin didn’t take Hitler’s statements on Lebensraum in the east too seriously.

Nevertheless, in the late 1930s Stalin put rearmament in overdrive, with clear intent to export the Revolution westward. On the one hand he feared to be drawn into a conflict the Red Army was not ready for, on the other hand he hoped that the confrontation between Fascism and the western democracies would turn ugly and weaken them both. He interpreted the Munich agreement (where the Soviet Union was conspicuously absent) as an attempt by the western democracies to turn Hitler on him and therefor afterwards sought a defensive alliance with them to counter that threat.

I was curious to see how Musial, a Polish political refugee in the 1980s, would judge the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact in 1939. After the German occupation of the remnants of Czechia in March 1939, Hitler recognised that France and Britain would support Poland against him, and that he therefor needed Stalin’s help to deal with Poland before that support could materialise.

In the end, Musial argues, Hitler had more to offer than Chamberlain and Briand. While the latter could only offer a defensive alliance (and they didn’t try very hard at that, although Musial doesn’t note this), Hitler could offer a partition of Eastern Europe in spheres of interest.

This allowed Stalin to expand into Poland, Finland, the Baltic States and Rumania. More importantly, Musial argues, after 20 years it again gave the Soviet Union direct access to Central Europe. It also set Hitler on a direct course of confrontation with the West, as a German attack on Poland was now ensured. From both sides, the deal was a calculated move that only served their own short term needs.

The winter war against Finland advertised the deplorable state of preparation of the Red Army to the whole world, and this sent waves of panic through the Soviet leadership. Full scale military reforms were enacted as a result. And although Stalin now had his hoped for war between the capitalist states, German success against France in May 1940 did little to ease the sense of urgency.

But by spring 1941 Stalin seems to have felt much more secure. Secure enough to talk confidently about a future confrontation and to make plans to recast the propaganda effort to prepare the party and the Russian people for an offensive war.

However, Musial doesn't end up condoning Hitler's attack in 1941 as a preventive war against Soviet aggression. Instead he argues that both Hitler and Stalin saw a confrontation as inevitable, and prepared for the final showdown. In due course, both sides misjudged each other, although in different ways.

German intelligence fatally underestimated the Russian rearmament drive, which led to surprise at the resilience of the Red Army in the summer of 1941. Making the decision to attack at that moment, the Germans aimed to get in the first blow while the Soviets were still weak. However, by 1941 the Soviets had recovered a bit from the 1937/38 repression and learned from the Finnish fiasco, as well as expanded the size of the army and production of modern equipment.

Stalin, on the other hand, assumed that no German leader would make the mistake of fighting a two-front war. This led him to dismiss the overwhelming evidence of the German build up as an attempt by the British to involve him in the war before the Red Army was ready. This meant that apart from being in the middle of a major reform, it was also unfavourably deployed and strategically surprised.

Musial’s account shows that the Red Army was in no state in 1941 to take the offensive, and that only in 1941 did Stalin & co decide that the time had come for the revolution to take the offensive. Although a date is never mentioned, Musial believes that the sources point to 1943 rather than earlier.

All-in all Musial brings together a lot of the new information coming from the Russian archives since 1990, some of which I hadn’t seen before. His view is broader than most military histories that focus on this period and discusses the logic behind many of the decisions made. That’s probably where the book will proves its worth and generate the most heated argument.

This review was posted earlier at Fortress Ameritrash

Monday, 18 June 2012

Byzantium by Martin Wallace - review

I consider Byzantium one of the best designs by Martin Wallace. Wallace has often tried to create confrontational games within limitations, while also retaining historical feel. His three player games often prevent two players from ganging up on the third. This is a difficult trick to pull of and Wallace gets it wrong at times, but definitely not in this case.

The game captures a crucial phase in the history of the Middle East (and the world). It's set around the initial expansion of muslim Arabs in the 630s, taking advantage of the weakening of the Byzantine and Persian empires after decades of war to the death. Players have the opportunity to shift their efforts between the Byzantine and Arab armies. Victory is most likely when these two sides remain balanced.

The board and pieces

The map includes present day Greece, Turkey, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Egypt, Cyprus and Crete (and areas in between). Byzantium reigns over the Mediterranean coast and Syria, the Arabs in Arabia and the Persian empire lies prostrate for its enemies to attack.

The board is nodal, ie represents the main cities, connected by roads. The three cities in Arabia can not be reached by Byzantine armies. There are several sea routes, to and from Crete and Cyprus.

The playing pieces represent armies, each player having a Byzantine and an Arabian army. Furthermore there are cylinders on every city, showing the level of population. There's also a number of cylinders in player colours, to show fortifications. The player maximum is 4.

There's also a set of orange blocks that constitute the Bulgars, who can descend upon Greece and Constantinople by player action.

Each player has his personal board showing areas for Byzantine elite units, normal units, city levies and logistics, and a treasury, the same for the Arabs. Since a player has only one playing piece for Arabs or Byzantines, the elite and normal units make up your field army. The city levies can be used to defend any town of that side. The logistics determine the movement of the field army. Smaller blocks are put on the board to indicate the size of the armies and logistics points. There is also an active action blocks pool, which can be used for placement on the main board. The treasuries can be used to buy new blocks.

The game board and pieces are all well up to standard.

Main mechanics

The essential features of the game are that each player can use both his Arab and his Byzantine army during a turn, and the use of the smaller blocks to perform actions. The former makes for a dynamic game, where players manoeuvre to defend their own cities and threaten those of others. Also the players have two score tracks for their Arabs and Byzantines. If the score on one track is twice as high as the other at the end of the game, the lower score doesn't count.

The latter mechanic puts a limit on the activities of the players. Turn length is not set, but determined by three players passing. If players have lots of blocks in the logistics areas and in the pool, the turn can take long. If players build large armies, turns will be short. There are three turns in the game.

The game is therefore about balancing: between Byzantines and Arabs and between the size of your armies and their activity. This feature works very well.

Players score victory points during the turns by capturing or taking control of cities, by building mosques or churches or at the end of the game by the number of city cylinders they control.

Actions

Players take actions in clockwise order. There are a many different actions a player can take.

- Take control of an uncontroled city. This is done by placing a small block of your colour from your active pool on the city stack. This mostly happens early in the game.

- move an army. This costs one block from your logistics area from one city to another, but three for a distance of two cities and six blocks for another step. Moving across water costs double, and even double that if another player blocks you by controling the opposite navy (ie the Byzantine navy blocks Arab armies and vice versa). Upon arrival at a city the player may attack it.

- activate the Bulgars. This is done by placing a block on an orange square on the main board. This strengthens the Bulgar units by two and allows them to attack. Initially this is at two points in Greece, but if successful the Bulgars could roam freely.

- build a fortification. This is done by placing a block on the appropriate square on the main board. Players have two cylinders to place on cities. These cities now have increased defense. Points scored by the Bulgars are added to the Arab score track.

- add one cylinder to a city. This is done by placing a block on the appropriate square on the main board. Three Arab and two Byzantine cylinders can be placed per turn. Cities have a maximum of three cylinders (or four if they have a fortification).

- control the Byzantine Emperor or the Arab Caliph. This is done by placing a block on the appropriate square on the main board. This immediately give you two VP on the appropriate track and a free elite unit for that army for the rest of the turn.

- control the Byzantine or Arab navy. This is done by placing a block on the appropriate square on the main board. This increases the costs of moving by sea for the opposite armies.

- attack a friendly city. This is done by placing a block on the appropriate square on the main board. It is normally forbidden for Arab armies to attack Arab cities, and likewise for the Byzantines. However, by taking this action, that restriction is lifted. One Byzantine and two Arab cities can be betrayed by their own each turn.

-Build a church or a mosque. This is done by placing a block on the appropriate square on the main board AND paying 6 gold from the appropriate treasure. This generates two VP on the corresponding VP track. Unlimited.

- Tax. Place any number of blocks from the active pool and receive 2 gold per block in the treasure of your choice. This is of course a way out when you are strapped for money, and can also be used to shift gold from one treasure to another, although not very efficiently.

- Buy new blocks. New blocks can be bought for three gold each. Arab gold can only be spent on Arab armies and logistics.

You can place up to three blocks per action from your pool to other spots on your own board. Also you can buy a maximum of three blocks per action. While you can put blocks with both Byzantines and Arabs from your pool in one action, buying blocks can only be done from one treasury.

Combat is fairly simple. Sixes on a dice are hits and the largest army remaining at the end of one round of combat wins, ignoring the casualties. This benefits larger armies, although they are not necessarily more effective (see below). A losing army retreats.

Attacking an army

When you move to a city defended by an army, it may retreat. If it doesn't both armies roll the following number of dice: one for each normal unit up to three, and one for each elite unit (no maximum). This gives an advantage to elite units, but they are more expensive in maintenance.

A defending army may always retreat before battle.

Attacking a city

When a player attacks an undefended city, the player controling the city may allocate levies for its defence if available. This is resolved like normal combat. Although the levies are unlikely to win, they may wear the attacker down. If the levies are dealt with the defending player rolls one dice for each cylinder in town (including the fortification). If this results in the attacking army ending up smaller than the city, the attacker retreats, otherwise the town loses one cylinder and forticifation and the attacker gains one VP and one gold (in the appropriate treasure) per remaining cylinder.

Constantinople is a special case. It cannot be control by a player and when attacked it rolls five dice and each six results in two casualties. This is potentially deadly as the Bulgars found out in one game. After eight casulaties they were effectively out of the game.

The game immediately ends if Constantinople is captured by the Bulgars or the Arabs. In that case only the Arab points are scored. Five extra points are scored for capturing Constantinople.

This is a possible kingmaker action. Any player within 5 points of the highest Arab score can propel to win by activating the Bulgars and capturing the capital. However, it is difficult even with all 11 Bulgar blocks on the board. Other players may choose to use the Bulgars on other ventures to make sure they don't attack Constantinople, or try to weaken the army by attacking it (or attacking other well defended towns).

Retreats

When an army retreats, it must end in a friendly city (ie. an Arab army in an Arab city). If it can not in one step, it must move through enemy cities and lose one block from the army per enemy city passd through.

End of turn

Actions thus continue until three players have passed. The first player to pass is starting player for the next turn, which is a benefit, because you can then pick useful actions as controling the Emperor of the Caliph.

At the end of the turn all your blocks from the main board (apart from those marking control of cities) return to your active pool. Half of the blocks lost in combat or other ways (rounded down) return to your active pool. Also, the players receive two gold for each cylinder. The income from Byzantine cities goes to the Byzantine treasury. Then the armies are paid from the treasury. Normal units cost one, elite three and levies two per block. If the army can't be paid, blocks must be removed to fit.

End of game

At the end of the third turn two additional points are scored per city cylinder (not the fortifications). The two tracks are then summed, provided neither is twice as high as the other. Highest score is the winner. In the case of ties, the largest number of cities under control decides the winner.

Evaluation

The feel is quite different from earlier Martin Wallace games, although it continues the indirect approach: players do not identify closely with any party in the conflict, like in PotR, where players are not the Italian cities, but condottierre that hire themselves out to the cities.

To me the game is challenging and highly enjoyable and I think it has the same range of strategies as Princes of the Renaissance or Struggle of Empires. It seems that the mechanisms drive players towards a balancing act between the warring sides and building up armies or keeping them mobile.

Two notes on strategy

About positioning your armies. In the best case you use your armies to corner part of the board. But at least make sure that you are not putting yourself in a spot where you are blocked by other armies and towns you cannot attack.

Building Churches or mosques. At two blocks and 6 money from your treasury for 2 VP, they are not very expensive. For context, for 6 money you have two blocks, so it effectively costs you 4 blocks. How many points can you score with four blocks in alternative use? Probably less. The only advantage of using them as army or action blocks is that you not only score points, but also take them away from others.

Sunday, 17 June 2012

A weekend's worth of gaming including Guards!Guards!

I also picked up a leaflet on Army Painter and I think there’s still a lot stuff I can learn about painting miniatures. Even though the intention is to outsource miniatures painting, a bit of handwork might still be necessary at times.

But the best part of weekend was the gaming itself.

On Saturday night we played a great management game about a financial institution trying to balance growth and risks. The mechanisms were really good, the material outstanding and the challenge daunting. Although we managed to expand out portfolio by a great number of mergers, we were late in getting rid of our risky assets, so at some point the regulators stepped in. Great game.

After that we tried Guards!Guards!, one of the two Terry Pratchett games released late last year. This edition is published by Z-Man Games. The game looks good, materials are good quality, the references to the Pratchett books are nice and the plot of the game is believable in the context of the Discworld novels.

The third or fourth time I´d been overrun by the Luggage

The third or fourth time I´d been overrun by the LuggageAlthough the object of the game is obviously to draw in the large fanbase for all things Pratchett, the game is not easy. There’s quite a lot of rules and there’s a lot to take in: movement, actions, volunteers, spells, that need to be collected, brought back to Unseen University and then there’s a challenge to be surmounted. And there’s dragons and cultists, and the Luggage, and saboteurs. Pffew! Indeed the game did prove longish and hard work. A trained crew could do it in 2 hours, but we didn’t get it finished in 2 and a half.

Not an unqualified success, but it is the first of the Essen 2011 games I had not played. A first milestone therefor on that project.

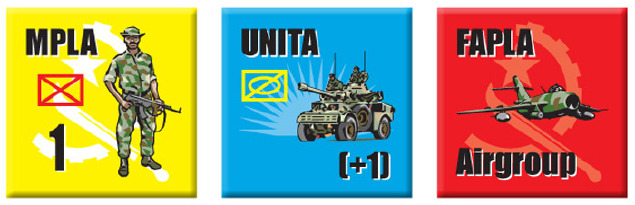

In the mail I received Angola, a rerelease of the 1988 version by MMP. It’s a four player game covering the 1970s civil war in that country with inspiring faction names like MPLA, FNLA, and UNITA.

Also, there was Eight Banners and Green Flag, about the Ming/Manchu army of the 17th to 19th centuries. I am still intreagued by Eastern armies, but I have no handle to take them on at this time. So this one will be on the stack but will not get read soon. This is a publication from the Pike & Shot Society, of which I'm a long standing but passive member. I have no problem, however, subsidising them and their excellent magazine Arquebusier.

Also, there was Eight Banners and Green Flag, about the Ming/Manchu army of the 17th to 19th centuries. I am still intreagued by Eastern armies, but I have no handle to take them on at this time. So this one will be on the stack but will not get read soon. This is a publication from the Pike & Shot Society, of which I'm a long standing but passive member. I have no problem, however, subsidising them and their excellent magazine Arquebusier.And finally, Too Fat Lardies has given July 30th for the release of Dux Brittaniarum! There's also suggestions that there may be a SAGA event in the Netherlands at some point, but that's in the "maybe, possibly' category as of yet. So get busy y’all!

Friday, 15 June 2012

The Hero of Waterloo? part I

William, then known as Prince of Orange, has a bad reputation in the English press, as many cock ups in the field are blamed on him. This new book (based on new research of primary resources from all participant nations) puts all that into a different perspective. It is supposed to be published in 2013 for the celebration of 200 years of The Netherlands. At some point (2014/5) the parts on the Napoleonic Wars are hoped to be published in English as well.

Looked at Geoff Wootten's Waterloo from the Osprey Campaign series, Haythornthwaite's introduction to Uniforms of Waterloo, Chandler's Campaigns of Napoleon and Hofschroers 1815 Waterloo Campaign, plus George Blond's La Grande Armee.

Chandler's book is still the standard work in English on Napoleonic warfare, even though published more than 45 years ago. You can easily trace his influence through other English accounts of the battle. However, the absense of German and Dutch sources (even those published in French) is a considerable limitation. Chandler can be a bit critical of Wellington when it comes to his deployments on 15th and 16th of June. The Prince of Orange only features in his narrative of Quatre Bras, not very condemning, so the negative attitude displayed by Haythornthwaite and Wootten must come from another source. I guess Siborne. It wouldn't be surprising if British officers after the war tried to put all problems at the door of a foreigner.

Haythornthwaite's book, first published in 1974, is of course more about uniforms and considering the references don't think the author did a lot of research on his account of the campaign and battle. No foreign language sources. The Brits are great, the Dutch-Belgians doubtful and William plain rubbish. Wellington of course can do no wrong.

Wootten ( the original publication is from 1992, I have a 2005 edition) still writes for a primary English audience but with more tactfull treatment of the allies. Book list not much improved on Haythornthwaite's. The Brits are still great, the Dutch-Belgians remain doubtful but William is now just inexperienced and doesn't seem to have so many battallions run down by French cavalry. He also notes that the Dutch held on to Quatre Bras in direct violation of Wellington's orders.

Blond's Grande Armee (published in French in 1979 and translated in 1995) hardly notices there being others than British at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, so wasn't much use.

Hofschroer (1998) is a different beast. It includes German, but also English and even a few Dutch sources. The Hof notes that William spend 2,5 years on Wellington's staff in the Peninsula and is therefor not totally inexperienced. Hofschroer mentions him generally in a positive light: leading the troops at Quatre Bras from the front, and doesn't point at his presumed mistakes. But as Hofschroer's objective is not a close description of the military events of the Anglo-Dutch army, William mostly appears as a conduit of Wellington's misinformation to the Prussians. Since the book is mostly a revision of English dominated historiography of the campaign, Hofschroer is critical of Wellington's conduct of the campaign and his dealings with the Prussians.

Thursday, 14 June 2012

Projects Big and Small

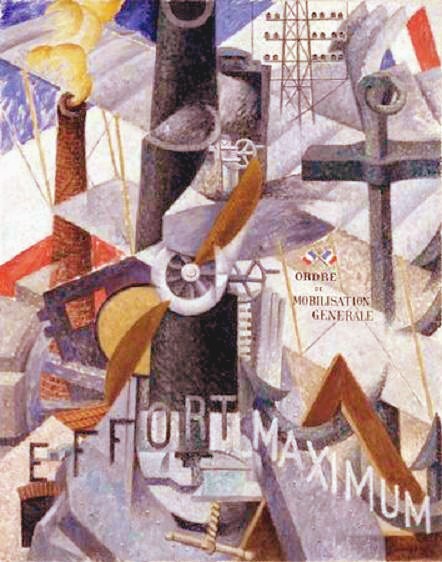

Grand Project: World War I Megagame, Maximum Effort

The main inspiration is Norman Stone's The Eastern Front 1914-1917 and thus focussed more on social and economic issues than the actual battles. It's too big, and it's not the kind of game people will want to play for a megagame, but I still keep looking for a way to make it work. Whatever, it's been a great stimulus for me to read an collect books on the war. Nick and I started a blog on the megagame two years ago and all my WWI stuff goes there, but I'll keep you posted on what happens there.

I've got a few smaller projects cut out to make it easier to digest the big one...

Mother Russia: this is the basic mechanism I have in mind for the megagame, but it should work better stand-alone. I've unashamedly stolen the mechanisms, but I think it will deal with economic issues of mobilisation in WWI very well. It has a social-political angle as well as all players represent groups in Russian society, negotiating their contribution to the war effort. Can Russian industrialists provide the troops with the necessary weaponry or do the rural gentry have a crucial role to play and can the peasants be fed?

Ypres: in April I visited the town and battlefield with a couple of friends and picked up a bunch of books about the battles in the area. I did a review of one of them, about the Belgian assault troops. I'd like to finish a few of the others as well and close it off.

Through the Mud and the Blood: I've got a few packs of 10mm late war French colonial troops with support for a company level miniatures game Through the Mud and the Blood by Too Fat Lardies. This will need painting and hopefully I can get some playing time after that.

Other minor projects

Barbarossa: this is in fact the left over of a serious project we finished in May. On the 26th of that month over 50 guys and a few women played a megagame through the opening half year of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. The Germans miraculously managed to take Moscow early on but didn't enjoy it for long.

I read lots of books in that time, but after a while couldn't keep up reviewing them or even finish them. So I will occassionally repost a review I've done elsewhere, but hope to finish off the remaining books, like the brilliant Absolute War by Christopher Bellamy.

Dark Ages Skirmishing in 28mm. I revealed this one earlier so take a look here

Vietnam: Jim Wallman's new Vietnam megagame Lost Youth will take place in London on September 15th. I hope to read a few books in advance, like Michael Herr's Dispatches and a book with the fascinating title The War Managers by Kinnard.

The Hero of Waterloo: a friend of mine is writing a book on Prince William of Orange, the future King William II of the Netherlands. He's asked me to take a look at the chapter on the Waterloo campaign, so I've (re)read some of my books with that question in mind. It's also forced me to get a better feel for the timing of events. William's greatest moment is at the Battle of Quatre Bras where his leadership overcomes the worst crisis of the campaign.

Leipzig Campaign in 1813: another project inspired by a megagame. There's vague plans to organise a rerun of Master of Europe in Germany in 2013. I need to brush up on this a some point, but it's distant future

King John: It all started on a lazy day in Rochester, and I'm fascinated by King John still. Obviously John was not a nice man, but as a statesman and military leader he's had a terrible press. I still fancy doing a game on the 1215/6 campaigns, or the revolt of Henry II's sons in 1174.

Essen 2011: Almost forgetting about the boardgames! Like with miniatures and books, there's a long backlist I'm not even getting to. So my first project is to get all the games I bought at Essen last year played. So at least one each month until October. Then I might get to the few more recent buys I've already played like Labyrinth.

A review would be nice by I don't think I'll get to the point where I've played the heck out of them and so can comment authoritatively.

Wednesday, 13 June 2012

Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords, or the origins of Anglo-Saxon kingship

"Strange women lying in ponds distributing swords is no basis for a system of government!" Monty Python

I picked up The Saxon And Norman Kings by Christopher Brooke about a decade ago in a second hand book shop in London and I remember reading it on the trip or soon after. I enjoyed it a lot then, as it's an interesting book and well written. That's also what made me read it again for my Dark Ages project.

It starts out, not with biographies, but an overview of how kings were selected, what they did, the origin of kingship etc. Only then it turns to the more conventional chronological narrative up to the ascension of Henry II and the establishment of the Angevin monarchy.

Central in this book is the matter of succession. The question was not as formalised as in the later monarchies, and elements of inheritance or royal blood, election and designatio by the incumbent monarch all played a part. Historians have disagreed about which element here was the most important. As time went by, Brooke holds, the royal bloodline became ever more important and even though the suggestion of election is always there, it is not likely that it played a big role.

Except of course in a few very controversial cases. The choices for Harold Godwinson in 1066 and Mathilda in 1135 clearly turn in a different direction with the backing of the most important barons in the land. But Brooke would argue that these are the exceptions that prove the rule. In all the rules seem to have allowed for a certain lattitude. While not all kings could claim all three elements of legitimacy, one or two could be enough when backed with force.

The book also shows the close links between the Anglo-Saxon kings and the church, which did a lot for legitimacy and their historical record. Great sponsors of the church are still better documented and better received than those that looked upon the church as a necessary evil or useful tool rather than a holy institution in its own right.

Obviously, this book was written without a lot of the archeological evidence available today and its far from complete. Nevertheless, it gives a good introduction to the age from an interesting viewpoint.

Tuesday, 12 June 2012

Minor Project: Dark Ages Skirmishing

Anyone who's ever played Avalon Hill's classic boardgame Britannia can probably understand the fascination of this period. Not only was Britain invaded by consecutive waves of invaders, there's also an epic quality to these small bands of adventurers carving out their kingdoms on foreign shores: Hengest & Orsa, Swein Forkbeard, Harald Hardrada and of course William.

On the opposing side are always the desperate invaders-turned-incumbents like Arthur, Offa, Alfred and Harold Godwinson. Their tragic fates lend a melancholy quality to the age.

You can also understand I was immediately taken in by the prospect of playing scenario based skirmishes with a limited number of miniatures rather than sizeable armies that would take ages to collect and paint.

I've ordered a German/Anglo-Saxon starter armer of 44 figures from Gripping Beast for Dux, and a first bunch of 40 plastic Vikings for SAGA. The miniatures are fine, and very good value for money as far as I'm concerned. I liked the Germanic sculpts better than the other Arthurian factions I think are interesting, like the Picts and Scots. Vikings are just the coolest miniatures around for SAGA.

Now, knowing my time restraints, I intend to have them painted rather than take that on myself. This is a big decision, but I think the right one. Time is shorter than money, so I need to outsource and focus on what I do best, which is reading.

This means I have a bunch of books stacked up, and as you could see in my previous post, it is still growing. There's a few Ospreys, to get me running, like the Anglo-Saxon Thegn, Vikings, Arthurian Fortresses etc. There's also a few books with interesting articles on Dark Age warfare and finally a few broader monographs on the Age of Migrations and the Anglo-Saxons. Most of the latter cover both the Arthurian and the Viking period, so that's efficient information collection, eh?

I hope to put on a first few reviews shortly.

Sunday, 10 June 2012

Back from Derbyshire

For some reason, Nick felt it was necessary to give me a copy of Garmonsway's Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. I've had much fun looking at the differences between the versions and sifting through the kind of stuff that would interest the monks that wrote it: the death and installation of popes, bishops and abbots. Never forget that most of our impressions of medieval monarchs are based on the opinion of ecclesiastics, who had their own axes to grind.

On the way back I dipped into the bookstore at the airport and couldn't resist a 3 for 2 Sonderangebot. The main inspiration was David Edgerton's book on the mobilisation of the Empire in Britain's War Machine. I got excited by the tables of British and overseas production as well as the maps of oil pipelines and major centres of war production. Topping that is the list of highest awards from the Royal Commission of Awards for Inventions! Edgerton weaves contemporary and newly made graphics very well and I look forward to reading it some day.

The Sonderangebot formed a pretext to buy two more books on Anglo-Saxons (my present minor project). On the one hand A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons by Geoffrey Hindley and on the other Simon Young's A.D. 500. A Journey Through The Dark Isles of Britain and Ireland. The former is a rather conventional history, while the latter is set up as a sort of fictional travel guide, written from the perspective of a Byzantine. That makes it a perfect background for a campaign set during the first Anglo-Saxon invasions. I hope to have more elaborate reviews of these books in the coming months.

Monday, 4 June 2012

Rear Guard Action

Read this bit only if you really care to know about me. If you're here for the games and military history the stuff below will prove boring and sometimes even frighteningly familiar.

This blog comes out of the realisation that trying to maintain a relationship with kids sucks up time like a black hole and that in good conscience you can't keep up the frantic rate of gaming, socialising, concert going and sporting you maintained as a bachelor. I'm still getting to grips with that situation after almost two and a half years, rather reluctantly.

At the same time I've started to realise that what I really like to do in life is play, read and talk about games and (military) history. I love that more than my job and more than concert going and sporting. I need money to live so can't quit working, so sporting and concert going have lost out. I've added almost 10 kgs in this period and I hate every single one of them.

And finally, my life is a graveyard of good ideas and hopeful starts. Very few projects get finished. That is something I want to change the most.

And then you turn forty. All these things come together and you face that crisis in a haze of organising a megagame while hosting a friends from abroad before running off to go camping. And a number of things you've been mulling for months need fixing. So you draw it up in a list. It means accepting that some things will never get finished or need to be outsourced. It means setting yourself goals to strive for rather than careering off into the dark future. It means stop using a rediculously outdated computer so you don't have to improvise all the time, you idiot!

So think of this blog as a rearguard action. An attempt to retain some of the ground lost to age and commitment (and lose some of the weight I've gained). Think of it as a means of putting dots on the horizon and enlisting the help of others to stay on course.

I'm going to turn these into a few Grand Projects and a few shorter ones with shorter time span. So my first posts will actually be more about detailing these goals: which boardgames do I break out first? What books do I review?

Perhaps I will do the occasional report on one of the few concerts I still get to go to. I might even whinge a bit about the weight of responsibility and my belly. But the main staple should be games and military history.