Robin Fleming’s

book is a great counterpoint to the political histories of the period. Because

of the archeological evidence the book is strong on demographic, social and

economic developments, and this allows stronger focus on the general population

and women in particular than the written record.

|

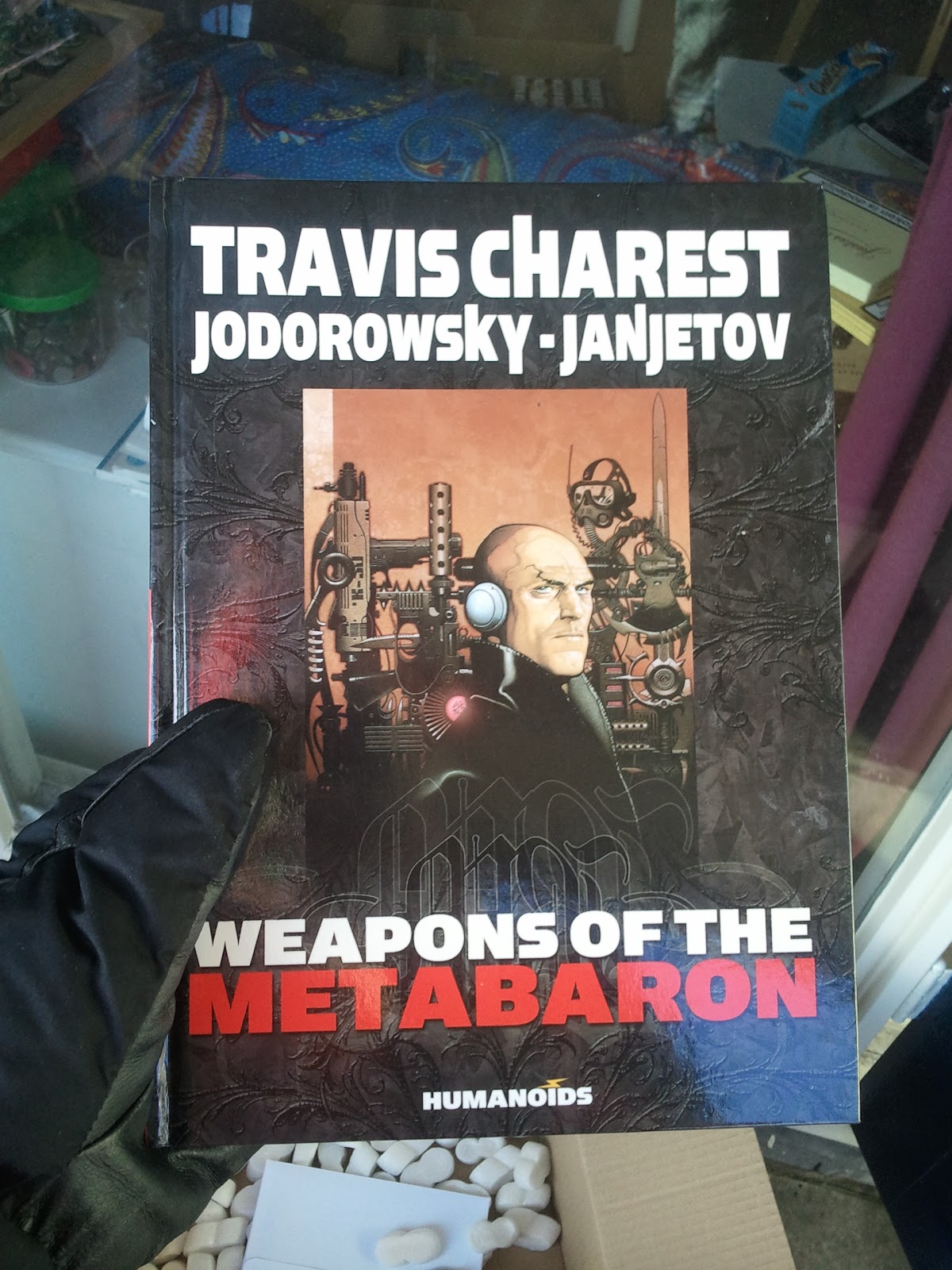

| My battleworn copy |

Especially

the last chapter is a showcase for the power of archaeology to (re)create real stories

of common people from physical evidence. The first part focuses on the high number of women

dying before their 35th birthday (often in childbirth) and its

effects on society, like the many orphans. The second part, recording

a live burial of a struggling woman suggests punishment or ritual burial of

slaves with their masters. And the last one shows the high death toll in towns

and the terrible hygienic conditions of people living close to their neighbours

and animals.

And there's a host of similar episodes spread around the book that I haven't got time to mention here, but give a fresh look at what we call the Dark Ages based on relatively new evidence. But while the

firm foundation in archaeology is the strength of this book, the long,

speculative interpretation occasionally becomes a grind.

The

archeological data frequently challenges the written record. Fleming suggests

that the coming of the ‘Saxons’ (as most scholars now accept, it was a very

mixed population of Germanic people from present day Northern France up to

Denmark) was a lot less violent than suggested by the literary sources which

were written later, sometimes centuries, than the actual events and who had

their own agenda. According to Fleming the kingdoms of the 7th and 8th

centuries used conquest myths to stress their legitimacy.

Archeological finds also point towards the conclusion that Roman economic

decline started a few generations before the legions left for the continent in

410. Population had been declining during this period and continued even faster

as Roman presence ended and political and economic fragmentation set in.

This

suggests in Fleming’s view that there was room for newcomers, while few graves from this period show violent deaths, nor a heavily militarised society. However, I think even

the smaller Romano-British population would maintain a claim to the land and it

is unlikely they would have relinquished it totally without struggle. Also, men dying on the battlefield would not be buried in their home villages.

The

newcomers mixed easily with the Romano-British. Based on

the lack of high status burials in this period, Fleming concludes that the 5th

and 6th centuries saw a remarkably egalitarian society. It also contained

a wide local variation of combinations of Romano-British and Germanic elements,

with individuals picking and choosing elements from different cultures to

create their own styles. Identities became very local, as opposed to the Romano-British elite which had focused on the fashions of its continental counterparts. The immigrants also, even though they described themselves as Saxons or Angles, were in fact leading very different lives from their grandparents.

Would social structures be imported from the

continent with the immigrants or would they assimilate into some sort of

‘melting pot’ as in the United

States in the 19th century?

From the

late 6th / early 7th century there are signs of economic

recovery and rapid political concentration. First, a few dozen regional powers

developed, which then coalesced into stronger kingdoms, like Mercia, that

dominated the others. However, the subjugated kingdoms retained a high degree

of independence. But the high level of competition forced all kings to find

ways to stay on top of the political food chain. This found expression in increasingly high status burials.

Kings

stimulated urban renewal by granting lands (hagae)

to lords and monasteries. Two new sources of income for kings in the 7th century were the tolls levied on town markets and industry, as well as coin

minting. The increasing number of locally produced coins found in hoards and around commercial buildings shows that money

returned to the economy.

Christianity

also offered several boons to ambitious kings. First of all, clerics could

provide a powerful administrative force to a king, increasing the utility of

his resources. Secondly, Christianity became a fashionable status attribute, and

as it became more accepted by powerful lords, it became expedient for their

followers and subjects to convert as well. This would lead to a chain reaction

of conversions down client networks. But the archeological evidence suggests

that many pagan symbols and rituals continued or were incorporated in Christian

burial rites.

While

during the 7th and 8th centuries the general tendency was

towards concentration and consolidation, the coming of the Vikings overthrew

the status quo. In certain parts of Britain it seems that regular

institutions collapsed, and in others it forced them to adapt to the crisis.

The coming

of the norsemen for example strengthened the power of the Saxon kings, as they found

clerical and secular lords more easily accepted their protection. In the 9th

century, the resurgent Saxons strove to bind the recovered territories more

firmly to them and transferred their institutions as well as their authority

(unlike the 7th century kings).

A major

new Saxon institution was the burh, the

fortified town. The support for protection of these towns was linked to

landholding. The burhs developed into

central places, combining trade and administrative functions, with the sheriff

(shire-reeve) as the representative of royal authority. Finds reveal commercial expansion and increasing sophistication.

While the

Danes had been able to bring a large area of England under their control, and

many of the erstwhile raiders settled, archeological finds suggest that the

norsemen mixed as easily with the Saxons and other people in Britain as the

Saxons had done with the Celts and Romano-British in the 5th and 6th

centuries. And again the genetic mix was matched by social and cultural

interaction that defies orderly generalisation.

Fleming

puts much store on bottom up agency and tends to interpret developments not as

the result of kings' decisions, but of social phenomena driven by local lords

and townspeople. Money in this period was not primarily a means of market

transactions, but a means to monetise tribute, so lords and kings could easily

buy status goods and pay for communal works. Local lords were able to impose

tribute on their subjects. The physical evidence for this development shows

more high status burials, suggesting more elaborate social stratification. By

the 11th century the Saxon thegn

had become more like a gentleman farmer than a warrior elite. That role was

increasingly played by royal household troops like the huscarls.

For

wargamers the eclectic mix of

genes, cultures and identities suggests that we have a lot of

freedom to create our own stories. In the fragmented and dynamic societies of

these two periods, any story we can come up with can probably have occurred

somewhere.

What chronicles call Saxons, could also be Franks, Frisians or even germanified Britons. Vikings can be Swedes but also assimilated inhabitants of the Orkneys. Clerics can be academic abbots sent from Rome but also local priests with little knowledge of the scriptures and their own ideas about dogma. Fact will often prove stranger than fiction.